|

Despite the fact that the word "sarafan" was adopted from Persian language, the clothing article itself was of the European origin. It came to Russia in the thirteenth century. An original name of the dress sounded like "feryaz'" (fe-RJAZ). This word means "a clothes of Feryag people" ("Feryag / Fryag/ Varyag" were ancient Russian terms for Vikings).

Originally, freyaz' was a MEN's clothing, a sort of a light coat. It is an unsolved ethnographical mystery, why and how a coat become a woman's dress.

Being a coat, a feryaz' had sleeves, and it was fasten with hooks or buttons, as a regular coat.

A freyaz' switched its name to "sarafan" not earlier than at the beginning of the fifteenth century. Scientists believe that "sarafan" is a distorted Persian word "serapa" - a honorific costume. But, despite changing its name, a sarafan persisted to be a man's coat, not a woman's dress, till the seventeenth century.

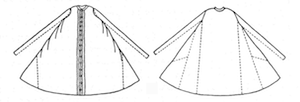

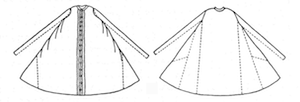

Let's take a look onto stages of transition between a feryaz' and a Russian sarafan as it is familiar to the public.

-

Sleeves gradually become a fake detail, and then disappeared at all.

|

|

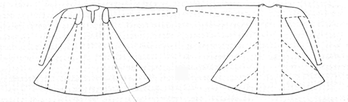

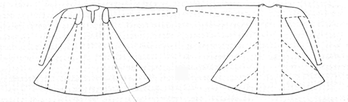

Sarafan with fake sleeves,

Ryazan region |

Sarafan with fake sleeves,

Perm region |

-

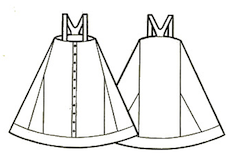

The front of an open coat-feryaz' started to be sewn – from neck to hips at first, and from neck to the bottom at last. A feryaz' become completely "closed" around the eighteenth century; however, residues of the former design persisted till the beginning of the twentieth century. Sarafans of 1910s had two vertical lines of trim marking the central line of the front (the former cut). Moreover, this "former cut" was decorated with buttons and fake buttonholes.

|

|

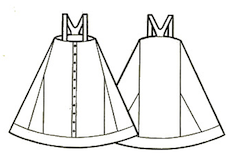

Sarafan,

Tver region |

Sarafan,

Smolensk region |

-

|

Sarafan, Ust-Zilma village

(North-Western Russia). A replica. |

Shoulders of a coat had gone narrower, and become straps finally.

-

A back part of a coat shrank, and, for Central and Southern Russia, disappeared completely. Only in Northern Russia and Baikal Lake region a sarafan's design with "a frog" - a small back part – persisted.

Untill the eighteenth century, the word "sarafan" was not natural for villagers. They preferred usage of local terms emphasizing either specific details of a cut ("klinnik" - made of triangles, "lyamoshnik" - with straps), or a material applied ("kholschevik" - made of homewoven linen, "kumashnik" - made of fabric-made cotton). And, the word "feryaz'" persisted till the seventeenth century at least in some regions of Russia.

|

Mrs.Kozoulina's great-granddaughter,

wearing Mologa-style faryas' |

Kapitolina A.Kozoulina (1906-1996), the keeper of tradition of Mologa region, speaks: "My grandma told that her grandma wore a dress named "faryas'". It was like a bathrobe with no sleeves, and it was sewn from neck to hips only: the bottom embroidered part of the underdress should be visible, because that embroidery was magical".

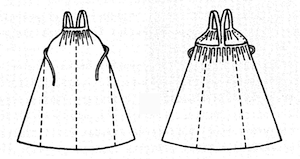

Sarafans, no matter what part of Russia from, all have a very thrifty cut. To make a dress flared, nobody cut a trapezoidal piece of cloth from a rectangle, disposing large side parts. Instead, village women took a rectangular basic piece, and attached multiple triangles to the base (remember "klinnik" - made of triangles). Or, contrary, an extra-wide rectangular piece of cloth could be taken, and a lot of tight folds were made on the upper (chest) side of a future sarafan, to fit a bust size.

|

|

Klinnik,

Kaluga refgion |

Dubas,

Perm region |

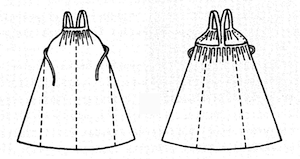

An everyday sarafan (actually, a working clothes) was sewn of very cheep materials, and was not too wide. Contrary, festive dresses were extra-wide, and were made of silk or/and brocade, and decorated with golden trim and pearls. Excessive width emphasized wealth of a wearer ("look, my family can afford a lot of expensive cloth just for my pleasure"). Also, in some regions, festive sarafans had fake sleeves (probably, it was a memory of feryaz').

As a rule, traditional clothing works not only as a clothing, but also as an ID. A sarafan tells you about:

|

Hemline of a sarafan.

The owner has three kids:

a daughter (the eldest child),

and two younger boys. |

-

wealth of a wearer's family

- where is this woman from.

- Any region (and, we daresay, any village) had its own features in cut, decoration, and usage of fabrics.

- A family status of a wearer.

- Sarafan's color was the main designator of status. Besides, in Southern Russia, only unmarried girls were allowed to wear sarafans (married woman had to put on poneva-skirt).

- In some regions, a decoration of a sarafan displayed quantity and gender of wearer's children.

- Daughters were honored with expensive and fancy (mostly, golden) trim. Boys were marked with straight and monochrome bands of cloth of a contrastive color.

|